Transfiguring World

Matthew 17:1-9

Six days later, Jesus took with him Peter and James and his brother John and led them up a high mountain, by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, and his face shone like the sun, and his clothes became bright as light. Suddenly there appeared to them Moses and Elijah, talking with him. Then Peter said to Jesus, “Lord, it is good for us to be here; if you wish, I will set up three tents here, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” While he was still speaking, suddenly a bright cloud overshadowed them, and a voice from the cloud said, “This is my Son, the Beloved; with him I am well pleased; listen to him!” When the disciples heard this, they fell to the ground and were overcome by fear. But Jesus came and touched them, saying, “Get up and do not be afraid.” And when they raised their eyes, they saw no one except Jesus himself alone.

As they were coming down the mountain, Jesus ordered them, “Tell no one about the vision until after the Son of Man has been raised from the dead.”

Peter is such a compelling character. Our beloved Daun Smith would always refer to him as a golden retriever— super enthusiastic and well-meaning, very loyal, but not always seeing the full picture. He did a lot of talking, blurting things out without really thinking things through. And his reaction to this spectacular vision on the mountain is a prime example of this. In seeing Jesus proven to be the Messiah, in seeing the figures of Moses and Elijah, in hearing God’s voice, he chooses to do something earthly, something familiar, something to try to hold onto the moment, to make it last. It is both not nearly enough, but also far too much for what he just witnessed.

And I think, to understand Peter’s motivations, we need to rewind a little, go back to just before this miraculous moment. In chapter 16, verses 21-23, Jesus tells is disciples plainly: “…that he must go to Jerusalem and undergo great suffering at the hands of the elders and chief priests and scribes and be killed and on the third day be raised.” Peter’s response to that is to rebuke him, and say, “God forbid it, Lord! This must never happen to you.” And Jesus rebukes him right back yelling, “Get behind me, Satan!” and calls Peter a “stumbling block.” Now, if we wanted to be really harsh towards Peter, we could be rolling our eyes and wondering why this person is one of Jesus’ closest confidants at this point—first he chastises the literal Son of God, is then referred to as a stumbling block, and he still has the audacity to, you know, instead of just sitting in revery and try to understand and take in this incredible moment, to try to do something. He always feels the need to do something or to say something. In this case, what he attempts to do is apparently so egregious, God God-self interrupts him to stop him from building these booths, these shrines, these memorial monuments to this moment that is so much more than a building could ever represent.

But let’s cut Peter a little slack. Let’s be a little more gracious and sympathetic. Let’s put this in perspective— Peter was just told that this person for whom he’s given up his life, this person he knows to be the savior (even if he doesn’t completely understand what that means), this person he loves with all his heart and soul and mind, has just told him he’s going to suffer and die. So Peter is dealing with some deeply troubling information here. He’s in denial, he’s trying to negotiate with fate, to negotiate with prophesy. He just wants his beloved Jesus to stay with him, just a little longer. Maybe this is some kind of anticipatory grief, as we would say in the hospice world. Either way, this need of Peter’s in the moment to build this monument, this memorial—misguided as it may be—comes from a place of deep love, and also, a place of deep loss. “It is good for us to be here,” he says, implying, “Let’s just stay.”

Last year, the author Lauren Markham came out with a beautiful long-form essay called Immemorial. The essay is Markham trying to cope with her own anticipatory grief, you could say—she’s trying to find a way to cope with her climate anxiety, climate despair, even, wondering what will become of this planet in this time of unprecedented loss. She realizes that there may not be a word for the thing she’s feeling, the thing she’s wondering about—a word for grieving something that’s not yet gone. And this search for a word or a phrase made her realize that she was not just looking for a word, but was aching to find a way to memorialize this feeling, to find a way aside from pictures on an iPhone, to create some kind of memorial or monument for this climate grief she was feeling. “If grief is the cavernous emotion nearly ubiquitous to human life,” writes Markham,

and mourning is the ritualized enactment of that feeling, then a memorial seemed to offer a space for both the feeling and its enactment to be made communally manifest in the physical world. Were there memorials to hold our climate grief? Maybe this was what I’d been longing for…

Like Peter, Markham was desperately trying to find a way to commemorate these deeply complicated and troubling feelings of confusion, of despair, of grief… trying to find a communal, earthly way to memorialize something so far out of our collective control. And like Markham, Peter is frantically trying to, whether he realizes or not, memorialize something that has not yet happened—he’s been told his beloved will suffer and die. And so he tries, with his friends, to create a structure to cope with this painful truth.

During Markham’s journey, she stumbles upon a strange organization called The Bureau of Linguistical Reality. And yes, this is a real thing. I can’t articulately describe it to you in my own words what this organization does, so let me just read what they wrote on their own website, in their own words:

We…playfully but believe sincerely that until we have the language to describe the changing world around us, we will not be able to fully grasp what is happening. To this end the The Bureau of Linguistical Reality is tasked with generating new words and inviting others to create new words that reflect our relationship to our rapidly changing environment vis a vis climate change and other [catastrophic] events.

So they’re coming up with new words, words that don’t yet exist, to make sense of a breaking and broken world. And in Markham’s interactions with one of the co-founders of this bureau, Heidi Quante, she explains her need to make some kind of memorial for the word she’s searching for. Quante pushes back. She says to Markham, “I don’t know that we need any more buildings.” She goes onto say that she generally finds much more meaning in ritual, than she does a static structure. Later on, when Markham meets Quante in person, she is still a bit stuck on this idea of constructing a memorial. Quante reiterates, “I feel like I keep encouraging you to think of memorial as something ephemeral, but you keep coming back to the physical.”

The reason Markham’s essay spoke to me so deeply isn’t just because I have some similar feelings of climate anxiety as she does, as I know thousands and thousands of other folks our age do—but she wrote much of this while she was pregnant and then a new mother. “There was a baby on the way,” she writes,

and I still had a catalog of worries about what life, the Earth had in store; all the birdsong she’d never hear, the fish she’d never see, the trees that would burn or desiccate long before she ever greeted them.

Chris and I knew we wanted to have a kid, it’s something we’d discussed from the beginning. We felt better about our choice after the 2020 election, hoping for a little, at least perceived stability help us feel more confident in our decision. Now Frankie is very much here, loved and wanted, in spite of things being more tenuous than ever. It’s difficult not to fret, not to feel incredible guilt sometimes, about the world I’ve brought her into. “Alive as climate grief is among so many of us,” Markham writes,

An overfocus on grief at the expense of current and future positive change can service as an immobilizer… It can become all about what’s already happened rather than what’s still possible, and it can become all about me: my grief, my feelings—my world.

Well intentioned as he may have been, this is what Peter was doing in this moment. He was doing what would help him in the moment, what would help him cope with this grief, his confused emotions and his lack of understanding. Instead of seeing what this miracle of Transfiguration for what it really was, he got lost in his own feelings and his own needs. Because the possibility present in the Transfiguration is one of future positive change. It is a possibility of what is to come, and what could be. Jesus will suffer and die, yes, but then, the part that Peter seems to not be able to hear, is that he will rise again and ascend. And this moment is a preview of not only of Jesus’ future, but of the possibility of an earth as it is in heaven. Jesus, showing his dazzling divinity in this moment is also showing that when we all truly understand, and therefore are living by his tenets—to love God and love our neighbor as ourselves—a dazzling future is possible.

But before we get to that point, as we get to that point, we mustn’t get bogged down in grief, in despair, in cynicism. We can’t think of all the violence and loss that happens around us in terms of what it means just for me. Rebecca Solnit, the writer and sort of go-to when it comes to having realistic and tangible hope in times of crisis, told Markham, when Markham told her she was pregnant, “You’re choosing the future.”

“My daughter is alive in a time of vanishings,” writes Markham, “but she too, is a creature of memory. Let our grief become fuel. Let us desire the world as it is.”

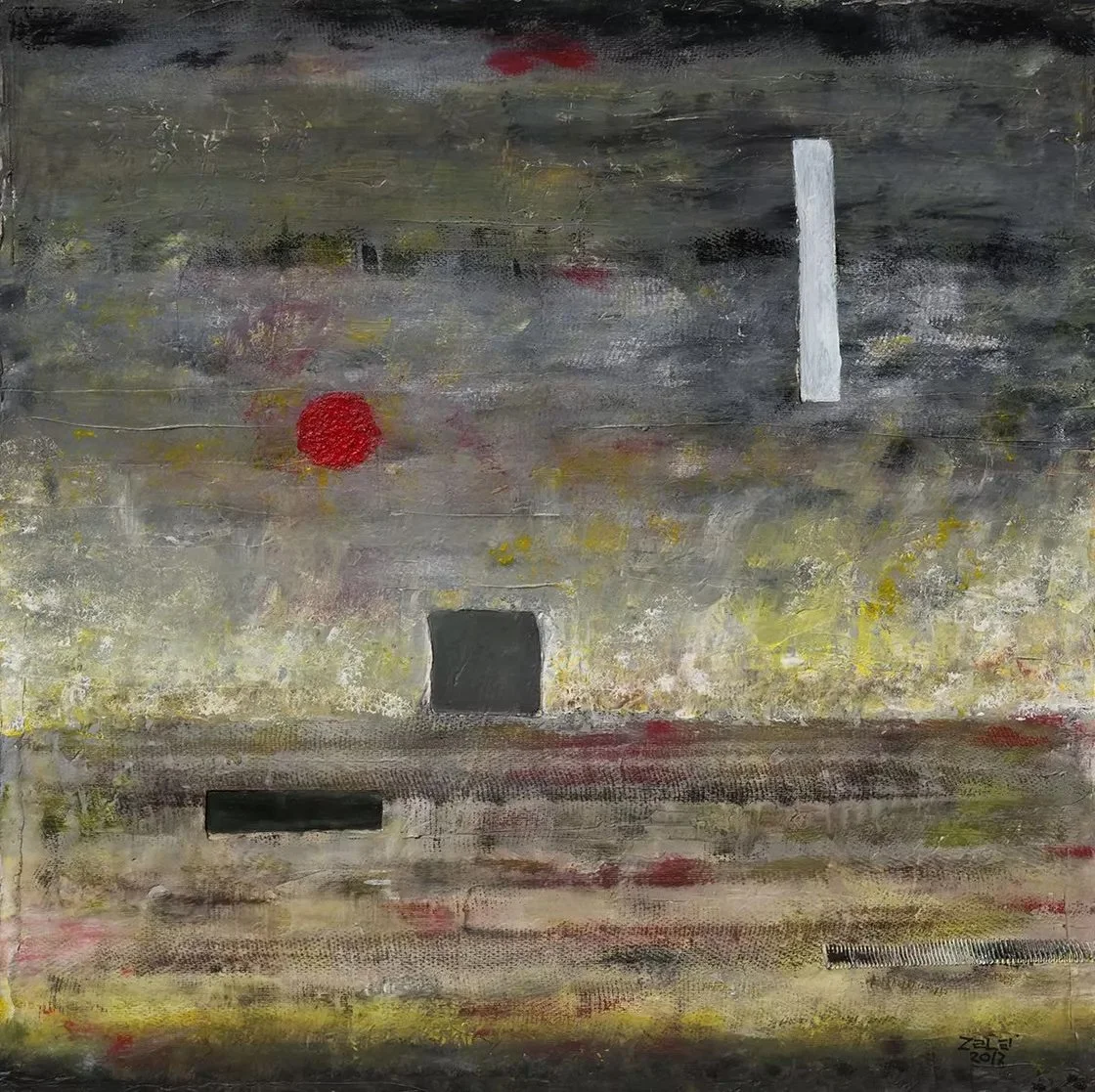

Whatever grief I had before Frankie, it has been transformed into something like fuel. It has been transformed, transfigured, if you will, into the hope that the world as it is, in all its brokenness, in all its tragedy, can be transfigured into heaven on earth. “It’s disorienting to move through a transfiguring world,” Markham writes. And when things are that disorienting, we get scared, and we fall back on familiar feelings and tropes; we get caught up in our own personal vicious cycles, rather than see the possibility in transfiguration, rather than feel hope in something completely different, in something brand new.

“Let us desire the world as it is.” When Jesus was transfigured on the mountain that day, he didn’t actually change. His essence didn’t change, his being didn’t change. He was then what he always had been, and what he always will be—fully human, fully divine, our savior, Creator, Christ, and Spirit, three-in-one. It was simply that he was revealed to his disciples, definitively, that this was the case. But in his disorientation, in his fear, and in his grief, Peter could only think of what had been—the transformative time he has spent with Jesus; he could only think of what would be lost with Jesus gone, instead of what could be gained with everything Jesus taught.

Lent starts this Wednesday. And it begins with meditations on death, on mortality, on how fragile and brief our human lives are; it would be easy to see this as something to despair. But that is not the point of Ash Wednesday, it’s not the point of Lent, and it’s not the point of our life as a Christian people. The point is to understand what a gift it is to be here, what a gift it is to take our call as Christians in the short time we have and really do something with it— for all those who will come after us, for this world that will keep going, keep changing, keep transfiguring into something different. And it’s up to us to accept that, and also to work with that fact that bend that change, that transfiguration into something good, into something dazzling and sustainable— to bend it towards an earth as it is in heaven.

Listen to him, God commands, to interrupt Peter’s attempt to commemorate the moment with a structure. And after this command from God that could be interpreted as a scolding, the first thing Jesus says to his disciples, the first thing they are commanded to listen to is, “Get up, and do not be afraid.” Listen to Jesus: do not be afraid. I don’t love the concept of giving up things for Lent— rather, I like the idea of taking up a new, life-giving practice; but I wonder if we could work on giving up this paralyzing and destabilizing fear that leaves us in cycles of anxiety or despair; I wonder if we could work on giving up our fears of a world that changes too fast to truly comprehend what is happening. I wonder if instead, we could desire and love this ever-changing transfiguring world for what it is. And I wonder if we could bend that transfiguration towards justice, towards peace, towards hope… and move forward to a bright and dazzling future. Amen.